Digital phenotyping sounds fancy, but the idea is simple. Your phone, wearables, and apps generate a trail of tiny signals. Sleep timing. Step counts. Screen habits. Typing speed. Voice tone during calls. Even though you move between places. When researchers and clinicians bundle those signals together, they try to spot patterns that line up with mood, stress, attention shifts, or relapse risk.

For adults, that pitch already raises eyebrows. For kids, it gets complicated fast.

Because youth mental health care is not a clean lab setup. It’s school pressure, family dynamics, trauma history, group chats, foster placements, messy schedules, and sometimes a child who’s doing their best while adults argue over what “normal” looks like. Add passive monitoring on top of that, and you get the big question: Is this a helpful support tool, or is it surveillance wearing a clinical badge?

Let’s sort it out without pretending it’s all good or all bad.

So what counts as “digital phenotyping” anyway?

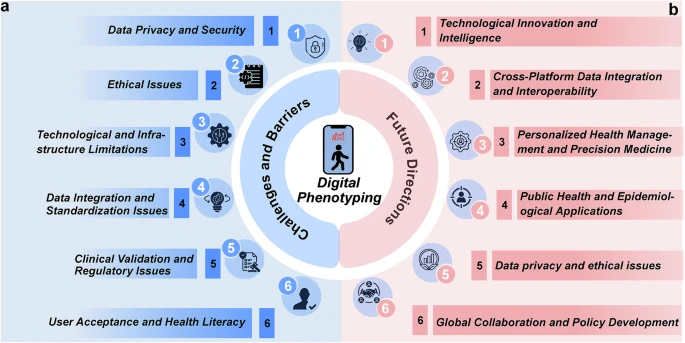

It helps to know what people are actually collecting. Digital phenotyping usually pulls from three buckets:

- Passive sensors: accelerometer data (movement), GPS (location patterns), sleep estimates, phone unlock frequency, app usage time.

- Behavior traces: typing rhythm, response latency, social engagement patterns, missed routines.

- Voice and language signals: changes in speech rate, volume, pitch variability, or word choice in journaling apps or chatbot check-ins.

Some tools are clinical-grade and consent-heavy. Others are just consumer apps that quietly collect a lot and then slap on a mental health label. That’s where trouble starts. “Mental health insights” can be real, but the business model often leans toward collecting more, not collecting carefully.

And for trauma-affected kids, “carefully” is the whole game.

The uncomfortable truth about data and trauma

Trauma changes behavior. It changes sleep. It changes voice tone. It changes how you respond to messages. It can look like depression, anxiety, ADHD, defiance, or none of the above. If you treat sensor data like a truth machine, you’ll misread a lot of kids who are protecting themselves the only way they know how.

The promise: when signals actually help kids and clinicians

Used well, digital phenotyping can support care in a way that feels practical, not sci-fi.

1) It can catch patterns humans miss

Clinicians don’t see kids every day. Parents may not see what happens at school. Teachers see one version of a child. The child feels something else entirely. Passive signals can sometimes show a trend that matches the kid’s lived experience.

A few examples that make sense:

- Sleep becomes consistently shorter and more fragmented for two weeks before panic spikes.

- Activity drops and screen time rises after contact with a triggering person.

- A teen’s daily routine becomes chaotic before self-harm urges return.

That’s not a diagnosis. It’s a heads-up.

2) It can reduce the “prove you’re struggling” problem

A lot of kids don’t have the words. Or they shut down in sessions. Or they’ve learned that talking honestly gets them punished. When care relies only on self-report, some kids get missed.

Signals can add context, especially if the kid agrees to track a few things and sees the data with the clinician. It can turn “I don’t know” into “here’s what changed.”

3) It can support step-up decisions without panic

When symptoms escalate, families get stuck deciding what level of care fits. Outpatient? Intensive outpatient? A more structured program? Digital signals can add one more layer of information, not to force a decision, but to guide timing.

And yeah, sometimes the right next step is a higher level of support, including structured addiction services when substance use is part of the picture. That’s where treatment settings like PA Drug Rehab can sit inside a broader care plan, especially when a teen’s coping has tipped into real risk, and the family system needs support too. https://arkviewbh.com/

The point is not “data says rehab.” The point is “data plus clinical judgment plus family context says we need more help now.”

The risk: when it turns into surveillance that breaks trust

Here’s the thing. Monitoring changes in relationships. If a child feels watched, they don’t feel safe. And without safety, treatment stalls.

1) Consent is not a checkbox when the patient is a minor

Parents often sign consent forms. Kids often live with the consequences.

For ethical use, consent needs layers:

- Parent or guardian consent for legal coverage.

- Child assent that’s real, not forced.

- Ongoing choice, meaning the kid can pause tracking without being punished.

If a teen thinks “no” will get them grounded, it’s not consent. It’s compliance.

2) Kids will game it, and that matters

If monitoring becomes a control tool, kids adapt. They’ll leave the phone in a different room. They’ll switch devices. They’ll change their behavior to avoid flags. Then the system produces “clean” data that reflects fear, not health.

And then adults say, “See, the data looks fine.” That’s how misinterpretation becomes harm.

3) Data can become evidence in places it was never meant to go

This part makes people nervous for good reason. Once data exists, it can be requested, shared, subpoenaed, leaked, or repurposed. Schools, insurers, courts, even family disputes. Not always. But the risk is real enough to belong in the decision-making conversation.

If you can’t clearly answer “who sees this and why,” you probably shouldn’t collect it.

Ethical guardrails that actually work in real life

If digital phenotyping is going to exist in youth care, it needs boundaries that protect kids even when adults are stressed, busy, or scared.

Guardrail 1: Collect the minimum that still helps

More data does not equal more clarity. It often equals more noise.

A good rule: if you can’t explain in one sentence why you need a specific signal, don’t collect it. For many kids, a few basics beat a surveillance net:

- Sleep window estimate

- Daily movement trend

- A simple mood check-in

Skip GPS by default. Location is sensitive, and it gets creepy fast.

Guardrail 2: Keep a clinician in the loop, not just a dashboard

A dashboard can’t ask follow-up questions. A clinician can.

Use signals to support sessions:

- “I noticed your sleep shifted this week. What was going on?”

- “Your routine changed after Wednesday. Was that a hard day?”

That kind of conversation respects the child’s context. It avoids the trap of treating data as a verdict.

Guardrail 3: Make the kid a co-owner of the data

If kids only experience tracking as something adults use against them, it fails.

Co-ownership looks like:

- The kid sees what’s collected.

- The kid helps decide which signals matter.

- The kid can annotate the data. “This dip was because my grandma got sick.”

- The kid can turn it off without retaliation.

That last part is hard for some families. But it’s central.

Guardrail 4: Build clear “what happens when we see risk” rules

Kids deserve to know what triggers an intervention. Otherwise, every alert feels like a trap.

Set a plan in plain language:

- What counts as a concern

- Who gets notified

- What the first response looks like

- What happens if the kid does not respond

- When emergency steps kick in

This is where digital tools can support crisis readiness without becoming a constant threat hanging over a kid’s head.

Bias and culture: the part that gets brushed off and shouldn’t

Digital phenotyping often assumes a default life pattern. Regular sleep. Safe neighborhoods. Stable internet. Quiet homes. One phone per person. That’s not how many kids live.

1) A “normal pattern” can be a privileged pattern

A kid in a crowded home might sleep in fragments. A kid in an unsafe area might not move freely outdoors. A child with caregiving responsibilities might have irregular schedules. Those patterns can look like “risk” if you don’t understand context.

2) Voice and language signals can misread dialect and culture

Voice-based models can mistake emotion. They can misread volume as agitation or flat affect as depression. Cultural communication styles differ. So do neurodivergent speech patterns. If you don’t calibrate for that, you build a system that flags the same groups again and again.

3) Trauma changes behavior in ways that mimic “noncompliance”

Avoidance, hypervigilance, shutdown, irritability, and sudden drops in engagement can be trauma responses. If your system treats these as “patient failing treatment,” you’re punishing symptoms.

So, culturally sensitive interpretation is not a nice extra. It’s the difference between support and harm.

How to use signals to support care without replacing it

This is the best use case: digital phenotyping as a sidekick.

Keep it in the “decision support” lane

Signals should answer questions like:

- Is something changing?

- How fast is it changing?

- Does the kid’s story match the trend?

- Do we need to check in sooner?

Signals should not answer:

- What diagnosis does this kid have?

- Is this kid telling the truth?

- What punishment fits this pattern?

If it starts sliding into policing, stop.

Pair signals with human check-ins that feel normal

Kids hate feeling like a case file. Small, predictable routines work better:

- Weekly short check-in message from a care coordinator

- A shared “what helped this week” note

- A clinician reviewing trends with the kid in session, not behind their back

Plan for substance use risk without turning the home into a monitoring station

When addiction risk enters the picture, families sometimes reach for strict tracking because they’re terrified. That fear is understandable. But full-time monitoring can still backfire.

If detox or stabilization becomes necessary, structured clinical settings can do that safely, with trained staff and clear protocols. For example, when families need a medically guided reset, addiction treatment in Jacksonville can be part of a broader plan that includes mental health care and family support. https://jacksonvilledetox.com/

The bigger idea: treat risk with care, not control.

A simple gut-check before you track anything

If you’re a parent, clinician, or program deciding whether to use digital phenotyping with a child, ask these questions:

- Does the child understand what’s collected and why?

- Can the child say no without punishment?

- Are we collecting only what we can justify?

- Who sees the data, and who does not?

- Do we have a response plan that protects the child’s dignity?

- Are we trained to interpret signals with cultural and trauma context?

- Are we using this to support care or to manage anxiety as adults?

If most answers feel shaky, slow down. You can still provide strong mental health treatment without turning a kid’s life into a sensor project.

Digital phenotyping can help. It can also harm. The difference is not the tech. It’s the guardrails, the intent, and whether the child feels respected while it’s happening.